Happy Morse Code Day

Okay kiddos. You think you have the knack of superior communication skills. How fast can you text your best friend? How many words per minute can you type on your Mac, your PC, or typewriter—if you even know what that last one is?

Yeah, you could pick up the phone and call them. You could also Skype with your colleges, but how did we get to this era of digital communication? It all started with a little electricity and Morse code.

A Little Telegraph History

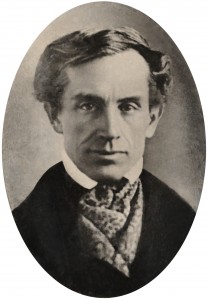

Samuel Morse (1791-1872) developed his code after traveling through Europe in 1832 and noticed some wooden windmill-like towers, called semaphores. Conceived by Claude Chappe, back in 1792, the towers used adjustable arms, placed in positions to correspond with the alphabet to communicate with each other.

These towers stood on hilltops about six miles apart, and messengers operating the semaphores would read each message by telescope and then pass it on to the next structure. Although this was faster than horseback, and you didn’t have to worry about where to hitch your ride, it definitely had its limitations. You could only communicate in daylight and in good weather.

Morse considered the limitations of the semaphores and began formulating an improvement to communication with the use of two new inventions, electricity and the telegraph.

In 1820, Danish physicist Hans Christian Oersted, discovered that he could manipulate a magnetized needle when an electric current passed through a surrounding wire. This sparked scientists and inventors across the world to begin experimenting with the principles of electromagnetism to develop some kind of communication system.

Sir William Cooke (1806-79) and Sir Charles Wheatstone (1802-75) of England developed a telegraph system with five magnetic needles that pointed around a panel of letters and numbers by using an electric current, in the 1830’s.

During this time, Morse, with the help of two other researchers, Leonard Gale (1800-83) and Alfred Vail (1807-59), eventually produced a simpler design. Using a single-circuit telegraph, that worked by pushing an operator key down to complete the electric circuit of a battery, they were able to send the electric signal across a wire to a receiver at the other end. With this device, they could send messages over long distances by using pulses of electricity to signal a machine to make marks on a moving paper tape. Voilà!—Simple, fast communication.

More On Morse Code

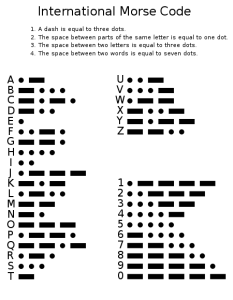

Communication is key, but not without a language. This is where Samuel Morse’s code came in. In 1838, he found a way in which to translate the dots and dashes the machine printed out into English. His original code used the dots and dashes to make numbers, and then assigned a particular number to a word or phrase in English. He soon realized how extensive and cumbersome it would become, so he substituted letters for the numbers of the old system.

Furthermore, he took the shortest sequences of dots and dashes and correlated them to the letters most frequently used. For example, the letter E is the most commonly used letter in the English language, and is represented by a single dot. This is like that final round in Wheel of Fortune, where the contestant picks five consonants and a vowel to solve the clue. They usually pick the most common letters of the alphabet.

Here is what the International Morse Code looks like:

The original telegraph machines made a clicking sound as they marked the moving paper tape. Soon, the paper became obsolete. Telegraph operators learned that they could translate the clicks directly into dots and dashes. It wasn’t long before operators trained in Morse code by studying it as a language that they heard rather than read from a page. And you thought speaking Klingon was cool.

The international Morse code distress signal (··· – – – ···) was first used by the German government in 1905. The repeated pattern of three dots followed by three dashes was easy to remember and chosen for its simplicity. This soon became SOS for short and was later associated with certain phrases, such as “save our ship” and “save our souls.”

During World War II, Morse code was critical for communication and used as an international standard for communication at sea until 1999. The Global Maritime Distress Safety System replaced the code, and takes advantage of advances in technology, like satellite communication.

Try It Yourself

Today, Morse code remains popular with amateur radio operators around the world. What, you don’t own a telegraph? Not to worry, you can practice online with a Morse code translator, by the White River Valley Museum. You can use a flashlight to send signals to your buddies at night.

Here is an example of one I did myself.

.- – …. .- – / …. .- – …. / – -. – – – -.. / .- – .-. – – – ..- – -. …. – –

You can hear what it sounds like here:

Can you figure out what is says? It just so happens to be the first message Morse transmitted from the U.S. Supreme Court to Vail in Baltimore. Morse and Vail demonstrated their electronic telegraph system to Congress, after Congress allocated $30,000 for an exhibition of their system along a 40-mile section of railway stretching from Baltimore to Washington. The message Samuel Morse wrote to Alfred Vail appropriately said, “What hath God wrought?”

Morse code is just one of the many great leaps we made in technology. It sped up communication, bridged geographical gaps beyond horses and trains, and aided in saving lives. It is also useful in entertainment.

Wimp.com posted a fun video segment from “Tonight Show with Jay Leno.” Morse code enthusiasts use the old technology to compete against modern text messaging. Teens get your fingers ready.

So, I wish you a happy Morse code. Celebrate how far we’ve come.

…. .- …- . / .- / -. .. -.-. . / -.. .- -.- –