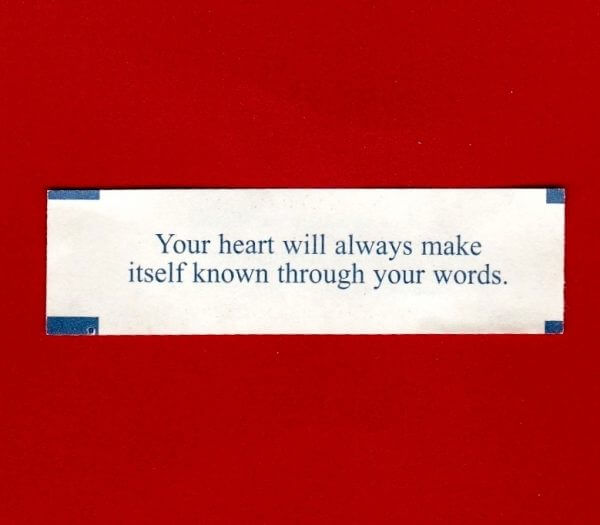

Fortune Cookie Friday: Write What You Know

It isn’t hard to find advice on life. People will give it out freely—even if you don’t ask. Much of it comes from experience and is passed down through the years. Some classic examples:

Two wrongs don’t make a right.

“‘Neither a borrower nor a lender be.’” – Polonius in Act-I, Scene-III in Hamlet by William Shakespeare.

“You can’t always get what you want.” – Mick Jagger

And then there’s this nugget from Vizzini in William Goldman’s The Princess Bride:

“‘Never go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line’!”

When it comes to writing advice, we can obtain it from various places. Search the web and books, and you will likely find some valuable tidbits that help you with your next work in progress. Well-known writers, agents, and editors pass on a litany of experience.

Show; don’t tell.

Kill your darlings.

Read lots of books in your genre of writing

One piece of advice that stumped me, in the beginning, was, “write what you know.”

This advice seemed to make sense for those that wrote non-fiction. The writer spent oodles of time researching a subject or was an expert in some field. They most likely knew everything there was to know about what they were writing.

I write fiction, usually fantasy, sometimes from an animal’s perspective. I have no idea what a squirrel is thinking while it scurries across the ground looking for a place to bury its nuts.

I also don’t know what it’s like to be chased by a monster, work in a forge, or have an evil demon tug at my soul, but I try my best at writing that in my current book.

Not every writer has experienced everything that happens to the characters they write in their books. Robert Bloch didn’t have a dissociative personality disorder like his Psycho character Norman Bates, and he certainly didn’t go around killing women in showers.

He based much of his work on his understanding of human nature from studying Psychology and events in World War Two. He found that “the real horror is not in the shadows, but in that twisted little world inside our own skulls.” He was able to write something scary because he understood fear.

J.K Rowling never flew on a broomstick in a Quidditch match like her character Harry Potter. The author explained that she needed a sport in her fantastical world because society needs things to hold it together, “cause it to congregate and signify its particular character…” She could easily pull similar feelings of thrill and amazement from her own life.

Perhaps she combined her experiences of a raucous sports event with riding in a car with the top down and wind blowing through her hair. We may never know, but we can feel the excitement because she felt it and wrote what she knew.

When we write what we know, we aren’t writing about events or experiences that happened exclusively to us. We are writing about our emotions. Much like method acting, we draw from our own experience that would give us a similar feeling. I may not have scaled a snowy mountainside, but I can imagine some of the feelings I would experience, cold, anxiety, sore muscles, and exhilaration upon reaching my goal.

With some extra research, we can transform our feelings from personal experiences into characters, settings, or plots. Everything we write will have a little piece of us in it, and that’s what makes it believable.

We can create that protagonist that the reader roots for as they struggle through adversity. We bring in multi-dimensional antagonists that readers love to hate. We produce just enough sexual tension to make the reader feel desire. We even write in humorous moments to lighten the mood and make people laugh.

Writers are those brave heroes, evil villains, romantic lovers, and funny comedians in our books. We are the creators of worlds and tellers of tales, and we do it from our hearts.